Language: English

Year: 2011

Pages: 275

Format: PDF

Size: 5.3 MB

An outstanding figure in the story of modern America, and central to the struggle of American patriots to take the country back to her founding principles, was the great industrialist and humanitarian Henry Ford Sr.

Ford was born on a farm in Wayne County, (near Dearborn) Michigan, on July 30, 1863, the son of Mary and William Ford, who had emigrated from Ireland in 1847. As a boy, Henry loved to do mechanical work with his hands. He attended rural schools only to the age of 15, when he found employment as a machinist's apprentice in Detroit. In his spare time he repaired watches and clocks to improve his knowledge of mechanical things, an interest that never waned. Even after he had become the master of an industrial empire, he delighted in disassembling the watches of his friends or joining the mechanics in his plant in a greasy repair job.

He was a deeply moral man, to whom honesty, work, and sobriety were sacred concepts. And he was a gentleman, in the true sense of the word, who, in the words of writer Albert Lee, "shared a love of all living things with naturalist John Burroughs and who shared campfires with his friend Thomas Edison. Ford was known to 'nail up a door for a whole season rather than disturb a robin's nest,' and he 'postponed [a] hay harvest because ground birds were brooding in the field.' He was a man of peace, saying .... that he would give his entire fortune if he could shorten [World War I] by a single day. "

Marxists hate Henry Ford. But most of the workers in his factories loved and revered him. He always displayed concern for the welfare of workers and believed fmnly in the dignity of work. In fact, it would not be an exaggeration to say that when Henry Ford began his seven-year long, 5 million dollar "lesson to the American people" in 1920, he was probably the best-loved living American.

...

In 1916 Ford led an ill-fated mission to stop the slaughter of World War I. He assembled a disparate coalition of clergymen, writers, politicians, pacifists, and businessmen, chartered the Norwegian ocean liner Oscar II and sailed for Europe in the hope of inspiring the neutral powers to mediate a peace treaty. His coalition squabbled among themselves, and the forces for war proved too strong. Ford returned to America a somewhat discouraged but wiser man. He never lost his distaste for foreign wars, however, and spoke out against them and the hidden forces that foment them in no uncertain terms ..

Mme. Rosika Schwimmer, one of the leaders of the Peace Ship project, was a Jewish diplomat and pacifist who, according to Ford,was more intelligent than all of the others aboard the ship put together. She tells the story of her first meeting with Ford, where he said "I know who started this war-the German-Jewish bankers." As he slapped some papers hidden in pocket of his coat, he said, "I have the evidence here-facts! I can't give them out yet because I haven't got them all. I'll have them soon!"

...

He purchased what was at the time a small weekly newspaper in his home town in Michigan, The Dearborn Independent, and turned it into his national voice, with nationwide distribution. His espousal of traditional values combined with a practical populism struck a chord with many Americans, for soon the sleepy weekly had turned into an influential giant, with a circulation at one point of nearly half a million. Ford lost money on the paper, selling it for five cents per copy or one dollar a year. When Jewish censorship kept it off the news-stands in some cities, he made it available through the local Ford agencies. He neither solicited nor accepted advertising-he would not have the paper subject to Jewish or any outside influence. The masthead meant what it saidindependent.

He gathered around him some of the most talented writers and

researchers in the business, virtually cleaning out the editorial staff of the

largest newspaper in the state, the Detroit News. He hired the best private

investigators and researchers. He employed the services of patriotic

Congressmen and diplomats. He despatched his agents to foreign

countries to dig up the facts.

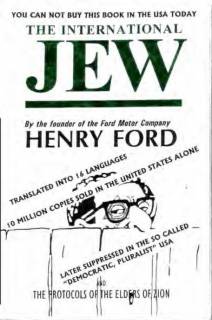

1920 marked the beginning of the publication, in serial form, of Henry Ford's research series in The Dearborn Independent. Each week, the paper carried a major story exposing an aspect of Jewish power and influence. One of the men Ford had hired away from the Detroit News, who would eventually become the head of the Independent, was the brilliant editor and columnist William J. Cameron. Cameron at first protested bitterly at the subject matter of the articles on the Jewish Question and almost bolted with a few other staffers who didn't want to touch this "forbidden" subject, but as the evidence began piling up, he became convinced that Ford was right. He was the author of most of the Independent's articles in this series, and stayed with Ford for the next 20 years. These articles would eyentually be collected in book form under the title The International Jew. The articles were a sensation and the book became a nationwide success, in fact one of the greatest best-sellers of all time. It was estimated that more than 10 million copies of the book were sold in the United States alone. The International Jew was translated into sixteen languages, including Arabic, and was distributed by the millions in Europe, South America, and the Middle East.

Naturally a terrific howl went up from the Jews, who carried out a campaign against Ford. Finally, under pressure, Ford stopped the circulation of the book. Jews and their friends went into bookshops and bought and destroyed all copies which could be found. Sneak thieves were commissioned to visit libraries and steal the book out of the libraries. This made the book so rare and unfindable that it became a collector's item.